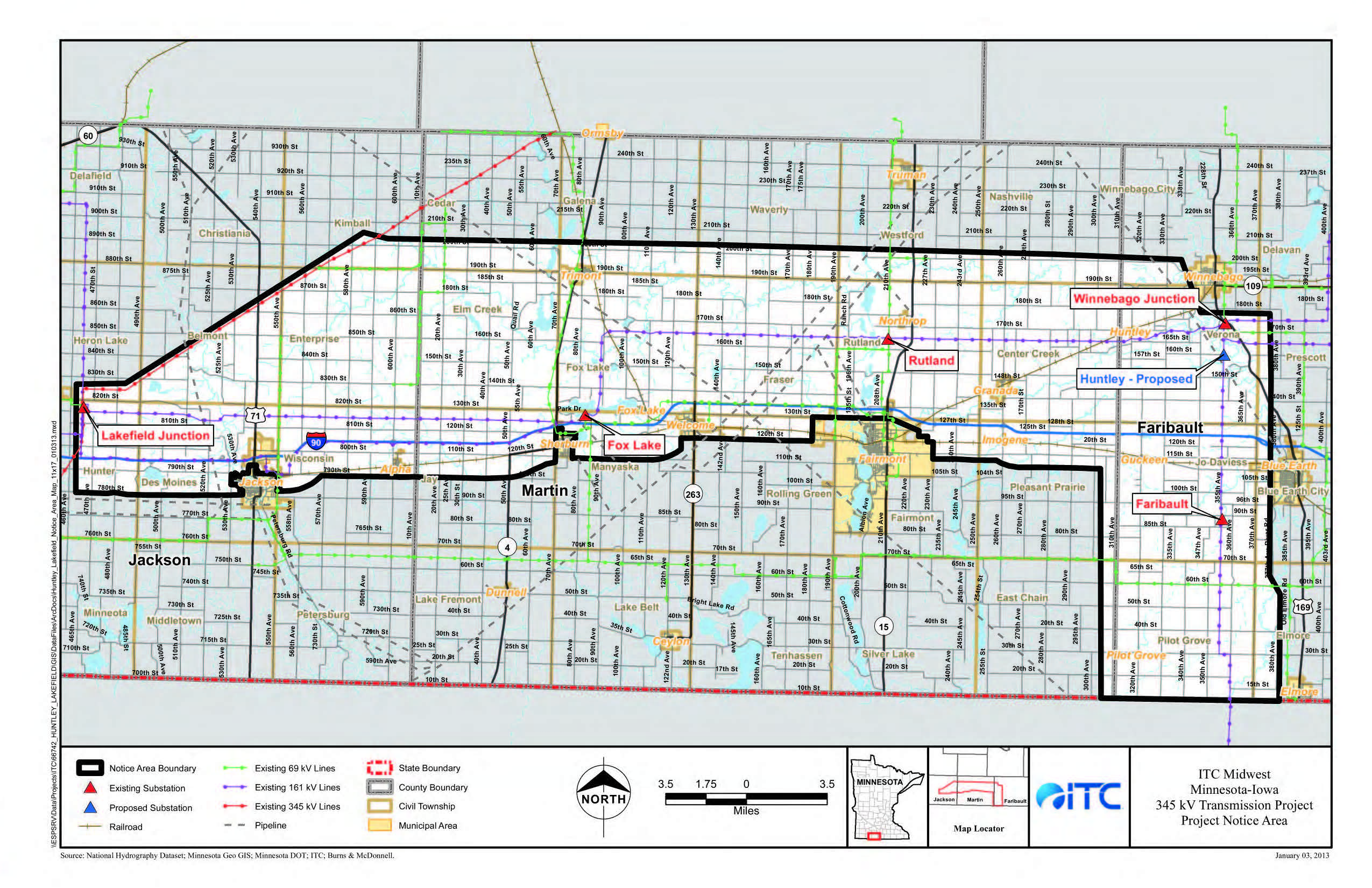

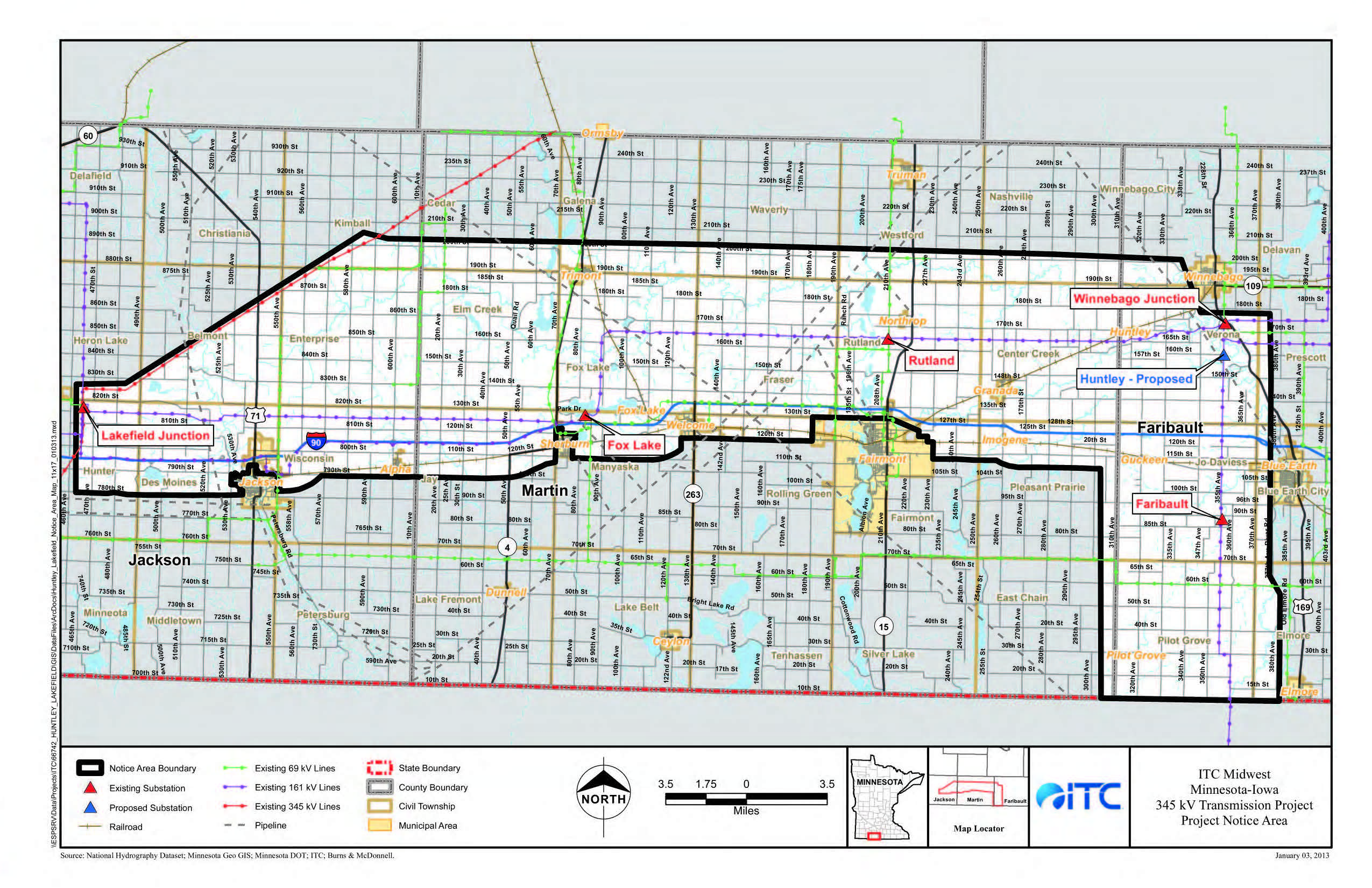

I’ve just spent the last week dealing with transmission need and routing, both primary issues in eminent domain and condemnation for transmission lines (well, two days, but prep before, and the aftermath likgers…). Here’s what the Wall Street Journal has to say, that “abusers are making a comeback.” Abuse? Well, how about Xcel Energy challenging landowners’ exercise of “Buy the Farm” under Minn. Stat. 116E.12, Subd. 4? How about ITC Midwest, a private transmission-only company, wanting to build a transmission line and thinking they have power of eminent domain in Minnesota?

Minn. Stat. 117.025, Subd. 10.Public service corporation.

“Public service corporation” means a utility, as defined by section 216E.01, subdivision 10; gas, electric, telephone, or cable communications company; cooperative association; natural gas pipeline company; crude oil or petroleum products pipeline company; municipal utility; municipality when operating its municipally owned utilities; joint venture created pursuant to section 452.25 or 452.26; or municipal power or gas agency. Public service corporation also means a municipality or public corporation when operating an airport under chapter 360 or 473, a common carrier, a watershed district, or a drainage authority.

Subd. 11.Public use; public purpose.

(a) “Public use” or “public purpose” means, exclusively:

(1) the possession, occupation, ownership, and enjoyment of the land by the general public, or by public agencies;

(2) the creation or functioning of a public service corporation; or

(3) mitigation of a blighted area, remediation of an environmentally contaminated area, reduction of abandoned property, or removal of a public nuisance.

(b) The public benefits of economic development, including an increase in tax base, tax revenues, employment, or general economic health, do not by themselves constitute a public use or public purpose.

An important consideration is how it’s defined in 216E.01, Subd. 10:

Wall Street Journal: Eminent Domain Abusers Are Making A Comeback: Cities and states are back to grabbing private property for the private profit of others.

By Dana Berliner

In Atlantic City, a state agency recently decided to bulldoze the home that Charlie Birnbaum’s parents bought 45 years ago and that he now uses as a piano studio and a base for his piano-tuning business, as well as renting out two suites. New Jersey’s Casino Reinvestment Development Authority wants to replace it with an unspecified private development around the Revel casino, which emerged from bankruptcy a year ago.

Mr. Birnbaum is represented by my organization, the Institute for Justice, in trying to save his business and his parents’ former home. He was served with condemnation papers on March 14, and the first hearing will be on May 20. After a lull in cases of eminent-domain abuse over the past several years, we are increasingly hearing complaints from home and business owners about government attempts to take property for private development projects.

If Mr. Birnbaum’s story sounds familiar, that’s because it is a repeat of what the Casino Reinvestment Development Authority tried in 1996. In that case the New Jersey authority tried to take the home of an elderly widow, Vera Coking, as well as Sabatini’s Italian Restaurant and a jewelry store, for a proposed limousine parking lot for Donald Trump’s Plaza Hotel and Casino.

The case garnered national attention and started a groundswell of interest in eminent-domain abuse. In 1998 a New Jersey district court denied the taking for the parking lot. Mrs. Coking stayed in her house for many years. Meanwhile, across the country home and business owners started resisting eminent domain. Courts began to take notice.

Then in 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled by 5-to-4 in Kelo v. New London that a whole neighborhood in the Connecticut town could be condemned on mere economic speculation—on the hope that new homes and businesses would be built in the same location and that these would produce more property taxes and “economic development.”

The decision shocked the nation. In the years that followed, 44 states changed their laws to make eminent domain for private development more difficult. State courts also stepped into the gap—nine high courts, including New Jersey’s, placed state constitutional limits on eminent domain. Chastened by this wave of opposition, most cities and agencies became much more careful in their use of eminent domain.

Unfortunately, this breathing spell seems to be ending. This latest condemnation by the Casino Reinvestment Development Authority is part of a new wave of eminent-domain abuse, as cities and redevelopment agencies try to regain some of the power they lost:

• California actually abolished its redevelopment agencies in 2011. Now cities and powerful development interests have launched a ballot initiative to restore the redevelopment agencies and greatly expand their power to seize properties for private projects.

• In Colorado, Denver suburbs and other cities have been on a spree of condemnations for shopping malls.

• Minnesota, Alabama and Illinois have added powers to state and municipal agencies to condemn for such projects as sports stadiums, industrial developments and business-district economic development.

• Philadelphia is taking an artist’s studio for a private development.

• A Louisiana port agency is taking one private commercial port to be replaced by . . . another private commercial port.

• New York never stopped abusing eminent domain—taking property for Columbia University, the Brooklyn Nets and the ever-present “mixed-use development” across the state.

This renewed eagerness to seize private property for the private profit of others comes despite its poor track record.

• Nine years after the Kelo taking in New London, Conn., nothing but weeds occupies the area once populated by more than 70 homes and businesses.

• The 22-acre Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn, N.Y., was supposed to include several office towers, thousands of housing units, retail, parks and other amenities to accompany the Barclays Center sports arena. But construction plans change, and the project will now include far less than originally promised.

• A thriving cigar and coffee lounge in San Diego was bulldozed in 2005, supposedly for a hotel. The space remains an empty parking lot nine years later.

The condemnation of Charlie Birnbaum’s building in Atlantic City is a classic example of eminent-domain abuse. The agency has no plan for the property. Promises of economic growth are made with no plausible substantiation of how it will happen. Mr. Birnbaum’s house is at the very edge of the area being taken and could easily be left alone. A judicial decision should come this year at the trial court, and the case is almost certain to be appealed.

The last outbreak of eminent-domain abuses spurred a grass-roots movement that seemed to chasten land-grabbing bureaucrats. With luck, these latest manifestations of government arrogance may prompt more pushback by home and business owners and result in greater private-property protections.

Ms. Berliner is the litigation director for the Institute for Justice, which represents Charlie Birnbaum, and represented the homeowners in both the Atlantic City eminent domain battle and the Kelo U.S. Supreme Court case.

Comments

Eminent Domain in WSJ — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>